Note to Self

Recently, The Athletic published an article about Michael Phelps, the worlds’ most decorated Olympian. But the story was not about his accomplishments as a swimmer. It was about journaling.

More about that in a moment. As I read the article, I began to reflect on my training as an architect and the tradition of carrying a physical sketchbook at all times.

There’s a pedagogy behind this practice. During a study trip to the Nordic countries one summer, a professor of mine pointed out that if you were sketching your surroundings in a purely pictorial way then you were missing the point. Analytical sketching isn’t about recording the view; it’s about extracting ideas for future use.

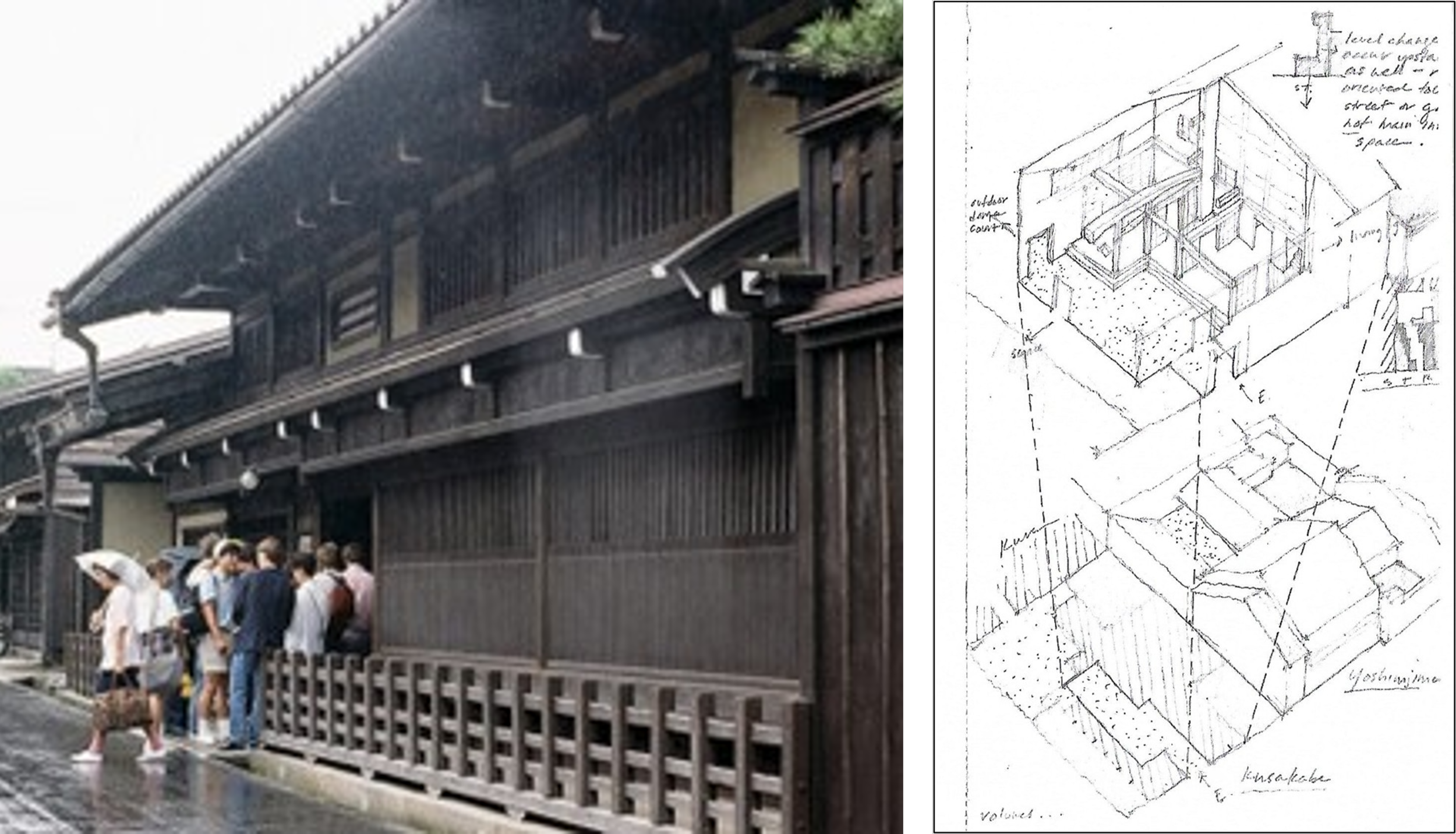

To remind myself what this looks like, I found some sketches that I made during a trip to Japan when I had students of my own. An example is shown here - an axonometric drawing of a 16th century Kyoto home that I made in order to examine the spatial sequencing from the street to the interior living areas.

It’s an imagined view, one that cannot be made with a camera.

This kind of sketching does more than just record information. It’s a method for discovering how things work. In a similar way, journaling is a method for understanding how we work.

In The Athletic article we learn that Phelps began to journal as a mental health exercise and it evolved into a powerful tool for self-awareness and self-actualization. Through a daily practice of transferring his activities, thoughts, and feelings onto paper, he creates space for identifying patterns. These in turn produce insights from which he extracts ideas for improving aspects of his life.

Today when I teach, I require that my students complete a semester-long journaling activity. It can be written, visual, or a combination of both. Whatever the format, the goal is the same: to learn how to capture data in such a way that ideas can be extracted from the information at a later time.

I make a similar request of my coaching clients. After experimenting with a new action or behavior, I ask them to pause and quickly note what happened so that they can recall the good and transform the not-so-good into something better the next time.

Whether we’re exploring the landscape of a city street or the landscape of our own minds, these acts of transformation prime the brain to think differently and solve problems more creatively.

The professor I mentioned earlier advised us to notice when we became tired while sketching. Fatigue is usually a sign that you’ve been laboring too long, with limited value added. Afford yourself the same exit strategy if you want to try journaling. Start with 10 minutes of free-form writing every day and focus on capturing just the essence of what you did, saw, thought, or felt. Then put down your pen – the ideas will be waiting there for you when you need them.